CATALOG NO. B103-2021

Two Moons

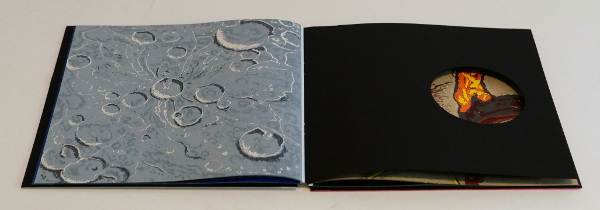

Two Moons, both covers

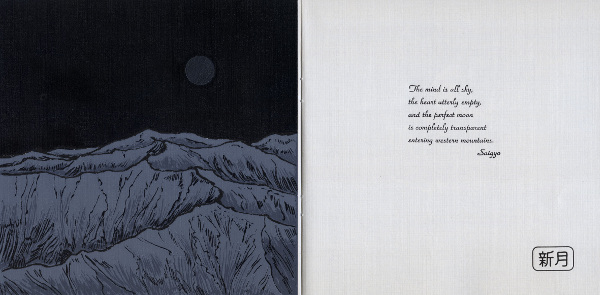

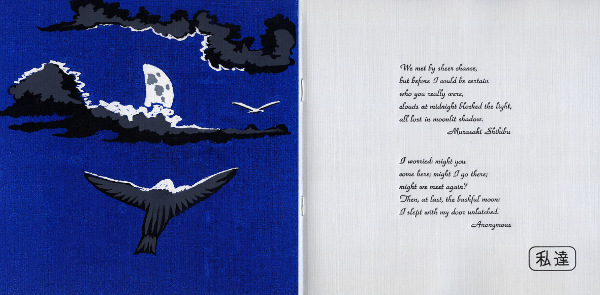

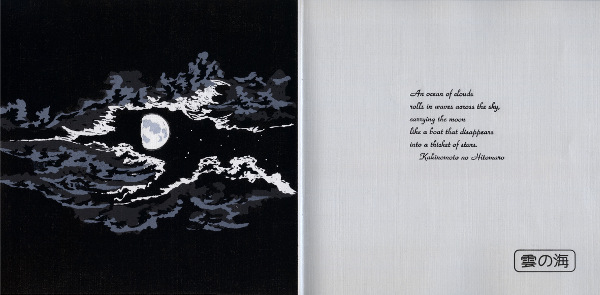

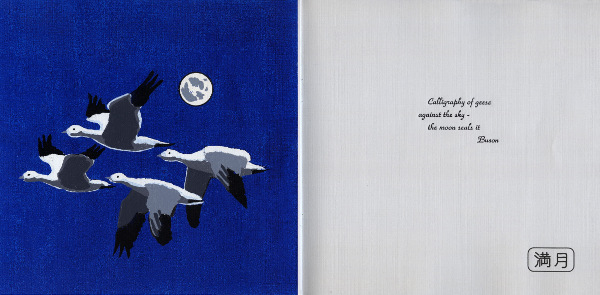

Two Moons is a 24-page artist book contrasting our serene moon, Earth’s lunar companion, with the fiery, volcanic Io, one of the four moons of Jupiter discovered by Galileo in 1610. Its modified dos-a-dos binding contains a literal window between the two sides of the book, which serves as their shared back cover. The side of the book on Earth’s moon is illustrated in cool blues, grays and black, and features seven impressionistic Japanese haiku and tanka that were written between the 7th and 18th centuries. The text on the Io side of the book focuses on the scientific data crucial to advancing knowledge of this distant body. The images, starting in tones of black and gray, continue to intensify in color, ultimately depicting the bright reds and yellows of Io’s fiery landscape.

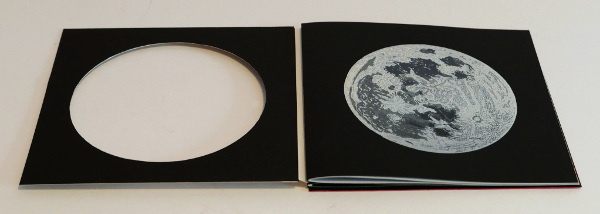

Earth's Moon, cover open

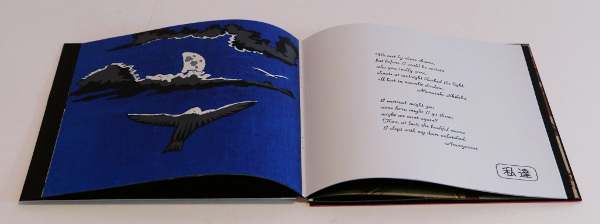

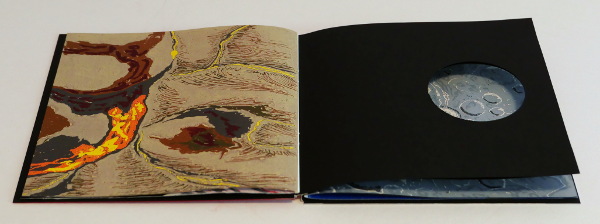

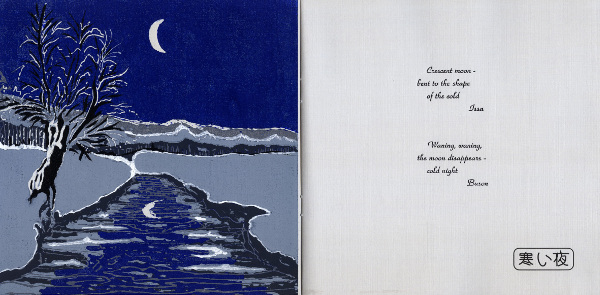

Earth's Moon, open

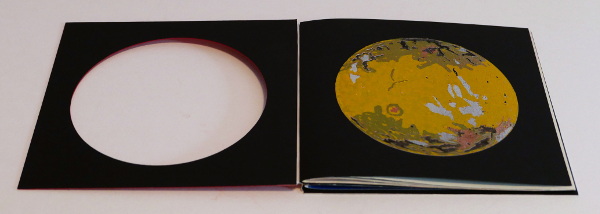

Io, cover open

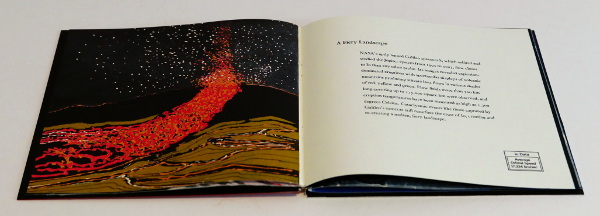

Io, open

Specifications - Edition of 15

Book - 8” x 8” x .6” Neenah Classic Linen, 24 pages

Covers - Painted and unpainted aluminum with cutout and paper liner

Spine - Washi Linen

Illustrations - 14 original images hand printed with Dremel-engraved polycarbonate plates and oil-based pochoir mylar stencils;

Inks - Oil-based relief inks and dry pigments in burnt plate oil; 79 color changes

Text - Hand set in Janson, Janson Italic, and Park Avenue; polymer plates. Letterpress printed

Case - Clear polycarbonate

Thomas Parker Williams - Concept, design, illustrations, plates, printing, binding.

Mary Agnes Williams - Concept, design, hand-set text (selected Haiku; Io text written by MAW), printing.

Collections

Permanent collection -

Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division

Swarthmore College McCabe Library, Special Collections

Center divider panel, Earth's Moon

Center divider panel, Io

Book pages

Two Moons Earth's Lunar Companion

Crescent moon - bent to the shape of the cold (Issa)

Waning, waning, the moon disappears - cold night (Buson)

The mind is all sky, the heart utterly empty, and the perfect moon is completely transparent entering western mountains. (Saigyo)

We met by sheer chance, but before I could be certain who you really were,

clouds at midnight blocked the light, all lost in moonlit shadow. (Murasaki Shikibu)

I worried: might you come here; might I go there; might we meet again? Then, at last, the bashful moon:

I slept with my door unlatched. (Anonymous)

An ocean of clouds rolls in waves across the sky, carrying the moon like a boat that disappears into a thicket of stars. (Kakinomoto no Hitomaro)

Calligraphy of geese against the sky - the moon seals it (Buson)

Poets -

Issa (1763 - 1827) Japan. One of the most loved poets in the haiku tradition.

Buson (1716-1783) Japan. A noted painter, he wrote visually intense poems.

Saigyo (1118 - 1190) Japan. An originator of Zen nature poetry.

Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (622 - 710) Japan. His grave is considered a holy place.

Murasaki Shikibu (973 - 1014) Japan. Her "Tale of Genji" is a literary classic.

Translators -

Pages 3a, 11 - Robert Hass; Page 3b - Stephen Addiss; Pages 5, 7, 9 - Sam Hamill

Io Fiery Moon of Jupiter

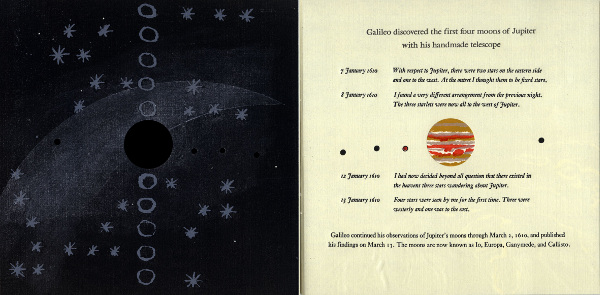

Galileo discovered the first four moons of Jupiter with his handmade telescope

January 7, 1610 - With respect to Jupiter, there were two stars on the eastern side

and one to the west. At the outset I thought them to be fixed stars.

January 8, 1610 - I found a very different arrangement from the previous night. The three starlets

were now all to the west of Jupiter.

January 12, 1610 - I had now decided beyond all question that there existed in the

heavens three stars wandering about Jupiter.

January 13, 1610 - Four stars were seen by me for the first time. Three were westerly

and one was to the east.

Galileo continued his observations of Jupiter's moons through March 2, 1610, and published

his findings on March 13. The moons are now known as Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

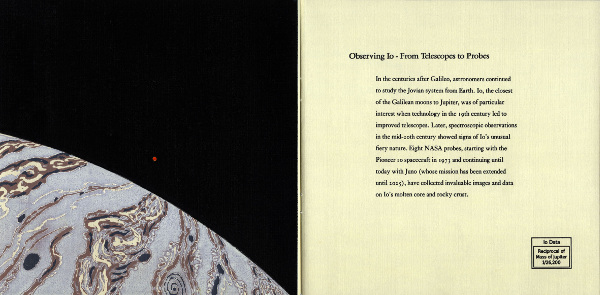

Observing Io - From Telescopes to Probes

In the centuries after Galileo, astronomers continued to study the Jovian system from Earth. Io, the closest

of the Galilean moons to Jupiter, was of particular interest when technology in the 19th century led to improved telescopes.

Later, spectroscopic observations in the mid-20th century showed signs of Io's unusual fiery nature. Eight NASA probes,

starting with the Pioneer 10 spacecraft in 1973 and continuing until today with Juno (whose mission has been extended until 2025),

have collected invaluable images and data

on Io's molten core and rocky crust.

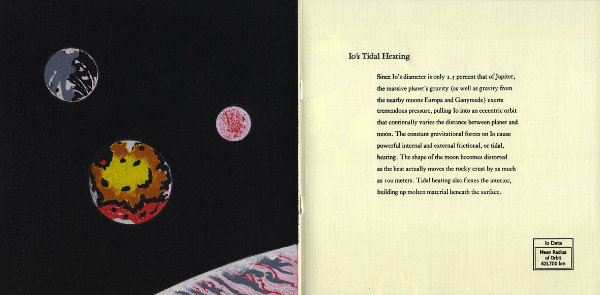

Io's Tidal Heating

Since Io’s diameter is only 2.5 percent that of Jupiter, the massive planet’s gravity (as well as gravity from

the nearby moons Europa and Ganymede) exerts tremendous pressure, pulling Io into an eccentric orbit

that continually varies the distance between planet and moon. The constant gravitational forces on Io cause

powerful internal and external frictional, or tidal, heating. The shape of the moon becomes distorted

as the heat actually moves the rocky crust by as much as 100 meters. Tidal heating also flexes the interior,

building up molten material beneath the surface.

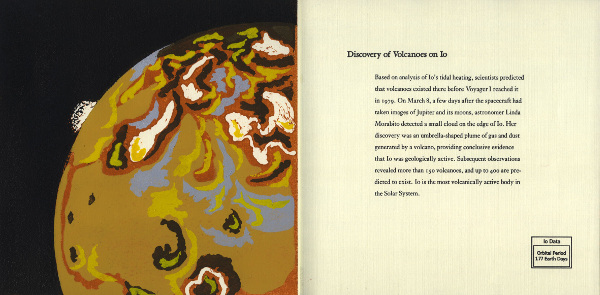

Discovery of Volcanoes on Io

Based on analysis of Io's tidal heating, scientists predicted that volcanoes existed there before Voyager 1 reached it

in 1979. On March 8, a few days after the spacecraft had taken images of Jupiter and its moons, astronomer Linda Morabito

detected a small cloud on the edge of Io. Her discovery was an umbrella-shaped plume of gas and dust generated by a volcano,

providing conclusive evidence that Io was geologically active. Subsequent observations have revealed more than 150 volcanoes,

and up to 400 are predicted to exist. Io is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System.

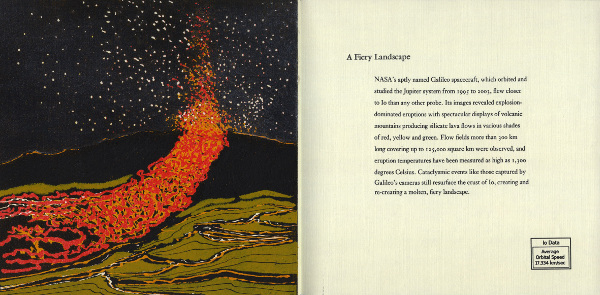

A Fiery Landscape

NASA’s aptly named Galileo spacecraft, which orbited and studied the Jupiter system from 1995 to 2003, flew closer

to Io than any other probe. Its images revealed explosion-dominated eruptions with spectacular displays

of volcanic mountains producing silicate lava flows in various shades of red, yellow and green.

Flow fields more than 300 km long covering up to 125,000 square km were observed, and eruption

temperatures have been measured as high as 1,300 degrees Celsius. Cataclysmic events like those captured

by Galileo's cameras still resurface the crust of Io, creating and re-creating a molten, fiery landscape.